Hamilton Arrives in St Andrews

Hamilton travelled to St Andrews to meet the archbishop January 1528. The hearing initially took the form of a conference between Hamilton and senior clergy. This was to last several days and Beaton allowed the accused to remain at liberty in St Andrews.

He was interrogated on the following theological points, on which protestant and orthodox doctrine had diverged:

- That the corruption of sin remains in children after their baptism.

- That no man by the power of his free will can do any good.

- That no man is without sin so long as he lives.

- That every true Christian may know himself to be in the state of grace.

- That a man is not justified by works, but by faith only.

- That good works do not make a good man, but that a good man does good works, and that a bad man does bad works; yet the same bad works truly repented do not make a man bad.

- That faith, hope, and charity are linked together, so that he who has one of them has all, and he who lacks one lacks all.

- That God is the cause of sin in this sense, that He withdraws his grace from man, and grace withdrawn, he cannot but sin.

- That it is a devilish doctrine to teach that any actual penance purchases remission of sin.

That auricular confession is not necessary to salvation. - That there is no purgatory.

- That the holy patriarchs were in heaven before Christ’s passion.

- That the Pope is antichrist, and that every priest has as much power as the Pope.

According to Spottiswood, writing in the 17th century, Hamilton said that the first seven were undoubtedly true and the rest should be held as true unless better evidence could show them to be false. These points, and Hamilton’s answers, were put to a council of theologians. In the meantime, he remained at liberty in St Andrews and was permitted to teach at the university.

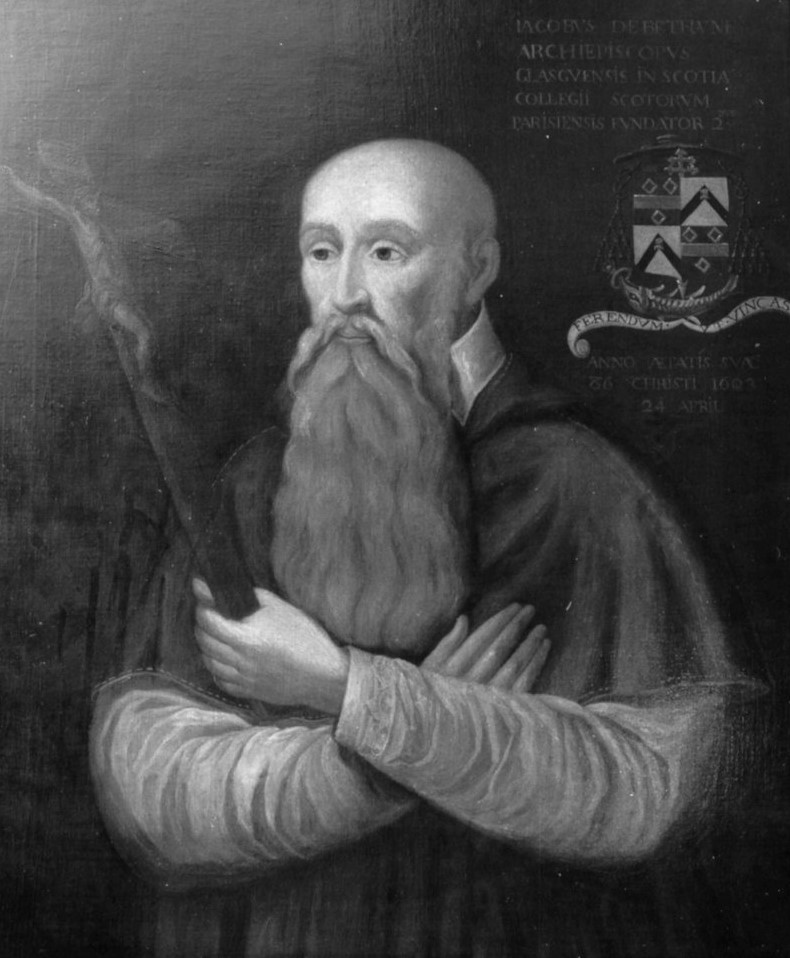

This was perhaps to allow him to further incriminate himself. More charitably, it has been suggested that Beaton was hopeful that Hamilton would again flee and make the proceedings unnecessary. Indeed, according to Spottiswood, the archbishop was not a cruel man. Nor should the faint family-ties existing between the parties be neglected; Beaton’s neice was married to Hamilton’s uncle.

The archbishop’s conduct was perhaps influenced by the more violent members of the clergy, including his nephew David, who later became Cardinal and whose own story as archbishop of St Andrews ended in bloodshed. Hamilton, however, appears to have been resigned to his fate. Before travelling to St Andrews he had predicted to his friends that he would soon be dead and he remained in St Andrews, faithful to his beliefs.

The Council of Theologians was made up of a large number of university divines and canonists: Master Hugh Spence, provost of St. Salvator’s College; Master James Waddall, parson of Flisk and rector of the University; Master James Simson, official of St. Andrews; Master Thomas Eamsay, professor of the Holy Scriptures; Master John Grison, theologue, and provincial of the Black Friars; John Tillidaff, warden of the Grey Friars; Master Martin Balfour and Master John Spence, lawyers; Sir Alexander Young, Bachelor of Divinity; Sir John Ann and, canon of St. Andrews; Friar Alexander Campbell, prior of the Black Friars; and Master Robert Bannerman, regent of the Paedagogium.

While the archbishop and his council considered the case, Hamilton continued to debate theological matters in public and in private. Alexander Alane, whose account provides us with much of our information about Hamilton’s trial and execution, was sent to dissuade him from heresy but was instead convinced by his arguments. A Dominican friar, Alexander Campbell, also entered into private conversations with Hamilton and, we are told, also privately agreed with him.

Further reading

Rev. Peter Lorimer, Patrick Hamilton: The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation, (London, 1857), pp. 139-145.